And we must see the things in the perspective they merit to be seen.

Courtesy Daily Greater Kashmir dt. Feb. 3rd, 2009 by Gautam Navlakha.

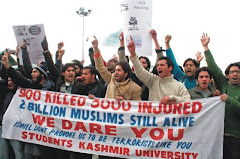

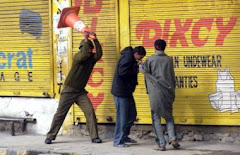

There were many firsts in the J&K state assembly elections of 2008. It was a seven phased poll, spread over five weeks, covering three winter weeks of December. A time when tens of thousands leave the valley for seeking fortunes elsewhere during winter months. An unprecedented deployment of 538 companies of central paramilitary forces, which included 388 companies of CRPF, were pressed in for election duty. This was supplemented by 60 to 70 companies of J&K police and Rashtriya Rifles, which were part of the security grid. Each phase of elections saw constituencies where polling was held, cut off through imposition of curfew in rest of the valley. Highways were blocked and non-residents of constituencies barred from entering. All separatists leaders, barring two who were placed under house arrest, were booked under the Public Safety Act to prevent them from campaigning against boycott. This despite the fact that canvassing for votes and campaigning for boycott form part of any democratic process. A phenomenal 1354 candidates stood for 87 seats i.e. on an average 16 candidates for each constituency. A large number stood for parties which have no presence in the state least of all in Kashmir and yet they spent money quite lavishly! Above all for the first time since 1990 militants, heeding the appeal of the people, halted all activities which could be perceived as obstructing people from casting their vote. Thus the extra ordinary security cover was grossly dis-proportionate to any threat posed by the militants or the non-violent boycott campaign. I believe that were all the faults of the election process i.e. electoral rolls which shows a higher proportion of voters for Jammu region than Kashmir despite Kashmir having 6.9 mn population in contrast to 5.4 mn for Jammu, 15-20 % of voters in Kashmir missing from rolls, 75-80% high voter turnout in border areas (Karnah, Uri, Langait….), lack of EPICs, mobile voters etc are counted then average electoral turnout becomes close to 35%. In other words a very large number, despite the extraordinary impediments placed against the movement, kept aloof . It would be foolish for anyone to ignore this or belittle this. Nevertheless, with these caveats in mind, it is true that more people did turn up to vote and this exceeded the 20% votes cast in 2002, in the valley. These elections also took place in the wake of agitation in Kashmir, and hindu dominated districts of Jammu region, for well over three months, which also saw a communalized response by the Indian state. They cracked down on agitators in Kashmir with brute force whereas they used kid gloves against the rabidly communal agitation spearheaded by RSS supported by BJP and Congress. This makes the larger than anticipated turnout in Kashmir quite remarkable. What should one make of it? It would be a mistake to read a relatively decent turnout in seven phased state assembly elections in J&K as rejection of the demand for self-determination. Not too long ago similar claims about demise of the movement were rubbished by massive non-violent assertion for 'azaadi'. Land transfer to the Amarnath shrine board, occupation of land by thousands of security forces camps spread amidst civilian habitations, economic blockade imposed by Jammu's right wing agitation has consolidated separatist sentiments. People joined of their own volition and it was their participation which persuaded the indigenous militants to silence their guns. Although protests were brutally suppressed in the valley, in contrast to the kid glove treatment of the Jammu agitators, the idea of 'azaadi' from India did not get eroded but remains a material force. It is, therefore, those who cast their vote pointedly de-linked assembly elections from their demand for self-determination. So why did they come out to vote?

Its common knowledge, that assembly plays little role in so far as future dispensation of J&K is concerned. It enjoys no authority over the most visible public issue of concern for people namely demilitarization of J&K. Going by PDP's experience of being part of a coalition government, upward revision of rent paid to the land owners, whose land is occupied by security forces, is about all they managed to wrest from New Delhi. State government is in fact powerless to even decide on its own to release political prisoners. All this falls in the domain of New Delhi's security apparatus. But they enjoy power to build roads, schools, health centre, create job opportunities, stop land transfers to non-state subjects etc. In short they can provide some material succor to a people who have suffered immensely for over two decades. Thus, people are wise enough to know that assembly polls do not amount to disowning the right of self-determination. The point is that elections to assembly in general, and the J&K assembly in particular offer a narrow range of prospects and people participate out of hope more than any other reason.

A watershed has been reached in Kashmir. Most significantly, if 1987 elections acted as a catalyst and tilted the balance in favour of armed resistance, then the summer agitation and elections mark a breach too. The equation between armed and non-violent resistance has again shifted. Catalyst for the shift in equation was the recent agitation in the valley, which brought closer home the political effectiveness of mass agitation. Indian state stood out as a callous brutish force against a non violent movement for everyone to see. Make no mistake, people continue to own militants as their own, have not disavowed armed resistance, and they continue to be wedded to the idea of 'azaadi'. In the midst of the long drawn out election process the killing of a Hizb ul Mujahideen commander Raees Ahmad Dar in Pulwama on 17th December saw more than ten thousand turn up for his funeral. Besides, one of the recurring feature of the election in Kashmir region was of voters pointedly claiming that they had not given up their desire for 'azaadi'. Even as fairly large number of voters boycotted arguing that they do not want to dilute their commitment by participating in polls. Apparent division between voters and boycotters are likely to erode rather than widen as time passes. Summer of discontent 2008 should act as salutary reminder against over-reading election averages and desire for 'azaadi' can scarcely be dismissed. So if the recent elections to J&K assembly carry any message it is that one should not take people for granted. Within limited options available to them they exercise their choice. Those who came out to vote in J&K comprised many who had also participated in the agitation. Between the assertion for 'azaadi', and the recent elections, nothing substantial happened to suggest that in the intervening three months things had improved. Instead brutal crackdown took place under Governor's rule. The experience of Governor's rule in the past two decades in general, and the recent one in particular, drove home the relative advantage of having even a weak kneed assembly over an all out repressive regime. An assembly maybe powerless to remove the security forces from amidst the people. But, in contrast to Governor's rule, it is relatively better placed to restrain an overbearing Indian security forces from brutalizing the people.

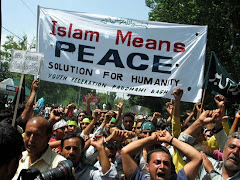

There is also a message for the movement. The linking of these elections with boycott, knowing that this did not amount to giving up of right of self-determination, was a tactical mistake and gave Indian state a propaganda advantage. The boycott campaign itself was not wrong as campaigning for boycott is perfectly legitimate. But investing it with high stakes as amounting to a virtual referendum for or against the movement, post summer agitation, was erroneous. It is true that separatist leaders and cadres were obstructed at every step. They were incarcerated and their voices gagged by forcing the newspapers from not carrying any news related to election boycott. But it is equally true that in the period heading towards elections they erred in their ability to propel the movement forward through an action program. In September-October Valley newspapers were full of news and comments about the absence of imaginative politics and fatigue setting in over frequent hartals. Juxtaposition of a non-violent assertion for 'azaadi' and participation in assembly elections reveals people's preference for politics of agitation. Recall the remarkable discipline and restraint exhibited by the agitators in the valley who have had to live at the mercy of Indian security forces all these decades. A people so brutalized could have given way, during the agitation, to anarchy and communalized frenzy or even snatched weapons from para military forces in the first few days of emotional outburst. Instead it became a manifestation for a collective affirmation of their desire for 'azaadi' i.e. for freedom from tyranny and oppression. This stood out in sharp contrast to the jingoism of the right wing hindu agitation in Jammu and their viciously bigoted behaviour, all under the benign gaze of the Indian state. Politics of hate and politics of assertion took place, so to say, side by side. All this makes imperative that people read the post-election situation soberly. PDP's vote and seat share has expanded and NC's base in Kashmir has shrunk. As an opposition party perforce PDP will espouse separatist concerns if it is to remain effective. Therefore, doing nothing is not an option for New Delhi. But playing a charade will make it worse. Composite dialogue with Pakistan and so called peace process never fired people's imagination even at the height of Indo-Pak bonhomie. They were not seen as paving the way for resolution, rather perceived as yet another attempt to arrive at a settlement between two contenders over the heads of the people. But even this process has halted. The cost of procrastination have only risen. On the other hand it is tragic-comedy to see the re-emergence of calls for pragmatism by talking about "internal sovereignty", "self-rule" etc which is nothing but reverting back to the failed four point formula of Pakistan's former military dictator Pervez Musharaf. Those willing to short-sell the movement will do a grave dis-service, therefore, by bickering amongst themselves and reviving call for 'adhuri azaadi'. A divided leadership pulling in different direction suits the Indian state perfectly. Ironically, this is just the wrong time for movement to dither. Indian state may not like it and they may be able to thwart emergence of Kashmir on international agenda for sometime. But there are far too many straws in the wind which points towards the fact that Kashmir is surely making its way into the world agenda. Besides, the stakes have been raised by Pakistani state which has referred to the "water crisis" which is "directly linked to relations with India" and to likely "environmental catastrophe in South Asia". At such a moment, a divided movement in J&K, needlessly getting sucked into debate about plebiscite as per UN resolution and independence, or self-determination versus negotiated compromise etc is immensely harmful. It should be clear to all, that those who see Kashmir from prism of 1947, as well as those who underline that in 61 years of Indian rule a strong popular desire for independence has emerged, ought to know that neither goal can be reached without the right of self-determination. Leaders and commentators who arrogate for themselves the right to negotiate away the rights of their people or speak of compromise have also not read people's mood since June 2008. They do not know that people want to exercise the right of self-determination and do not want this to be bargained away.

But by far the biggest challenge is posed to the Indian state. Enlightened self-interest suggests that allowing people to determine their destiny, in so far as future dispensation is concerned, makes for an attractive democratic closure to a 61 year old dispute. This could augur well for Indian democracy and south asian regional cooperation. But with Indian policy and opinion makers in a celebratory mode and blinded by their own propaganda that back of the movement has been broken and people subdued, likely course of action will be little bit of the same old prevarication. The Omar Abdullah government has already resiled from talks (CM claimed that everyone will have to wait till after the parliamentary elections are over and new government settles down i.e. six to eight months away) and from autonomy (because its coalition partner Congress is opposed to this they have stepped back from their stance). If New Delhi is not clear what it wants and having sold these elections as its success story likelihood of even empty talks renewing anytime soon is remote. Fact of the matter is, however, longer Indian state delays more difficult will it get for them to dictate the course of events. It is this dilemma which stares at India. So those who feel down and out after elections ought to know that what seems to be need not be what it appears to be. The message and meaning behind appearance and reality are very different. Real meaning is the need for a politics which reinvigorates unity around the right of self-determination and takes it forward.

No comments:

Post a Comment